How Far Would You Go

For the Girl of Your Dreams?

Some novel writers plan everything in advance. They are the plotters, the outliners. Ideally, the challenges, defeats, and triumphs of their protagonists arrive at precise times, creating a smooth-flowing product that keeps their readers turning pages late into the night. The plotters’ extensive planning comes with a downside: if too rigidly followed, it impairs the addition of fresh ideas.

Pantsers, also known as discovery writers, are the extreme opposite of pure outliners. They write “by the seat of their pants.” They invent their characters on the fly, throw them into hot water, and wait to see what happens. What a thrill! Due to structural weaknesses, pantsers often require more revisions of their manuscripts.

What should pantsers do when they get stuck writing a scene? They have no outline to guide them. Steven James, author of Story Trumps Structure, recommends they ask themselves four questions.

First, “What would my characters naturally do?” Second, “How can I make their situation worse?” Third, “How can I add a pivot point?” And finally, “What promises have I made to my reader that I have not yet fulfilled?”

At the end of my post titled “Bow-and-Arrow,” I wrote, “Tune in next month when TAT asks, ‘How far would you go at age nineteen, at the local swimming pool, to win the attention of the girl of your dreams?’” That was September 28, 2023. It’s time TAT fulfilled a promise to his readers.

Were you nineteen once? Perhaps you are even younger now. You only wish you were so old and wise. How eager you are to be free, to experience life to the full, to “live and learn!”

I, TAT, met Lori Wendt, my bride-to-be, on the first week of our freshman year at Alma College. We were at a Bible study with twenty other students in the very chapel where we married on June 15, 1991. As a man of action, I wasted no time. I introduced myself to Lori immediately and walked her back to her dormitory. There we stood next to a large rock and talked for an hour. Somehow, that immovable stone embedded itself into my mind and became the first symbol of a better stone to come.

Lori had always wanted to become a veterinarian at Michigan State University but in a stunning reversal of plans, she changed her mind and reluctantly followed her elder sister to Alma. I learned that day that Lori was a skilled musician, proficient on three instruments, and planning on becoming a teacher. She had just become a Christian that very year.

I dropped Lori off at her door and said goodnight, but within thirty seconds, I was already considering that I might marry her after graduation. I’d never imagined such a thing before. I promptly bought her a “Thompson Chain Reference Bible” and inscribed it with ink, mentioning the value of the Thompson Chain. My subtlety escaped her. Next, I bought her a copy of CS Lewis’s Mere Christianity.

We walked on golf courses late at night beneath the moon. She didn’t know that “shooting stars” were simply asteroids burning up, and I found that endearing. She learned about the heavens from me, and I learned about music from her.

I had memorized many poems, including “She Walks in Beauty” by Lord Byron:

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes.

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

I recited my poems for Lori, but she didn’t think too much of them. She was dating some older man, a musician, which was clearly not in my favor. He even had his own airplane. On the other hand, he didn’t live nearby; I lived 200 yards away.

Lori broke up with that first musician and started dating another one. He, too, lived far away, which was very good, but something about my approach wasn’t working. My message was not getting through. How could I take it up a notch without being too overt?

Spring arrived in 1988. Many of our mutual friends were heading to the college pool. Lori, herself, was going, and that’s all that mattered.

Lori swam laps. She was like a musician at practice with her metronome, focused on the exercise. No time for talking.

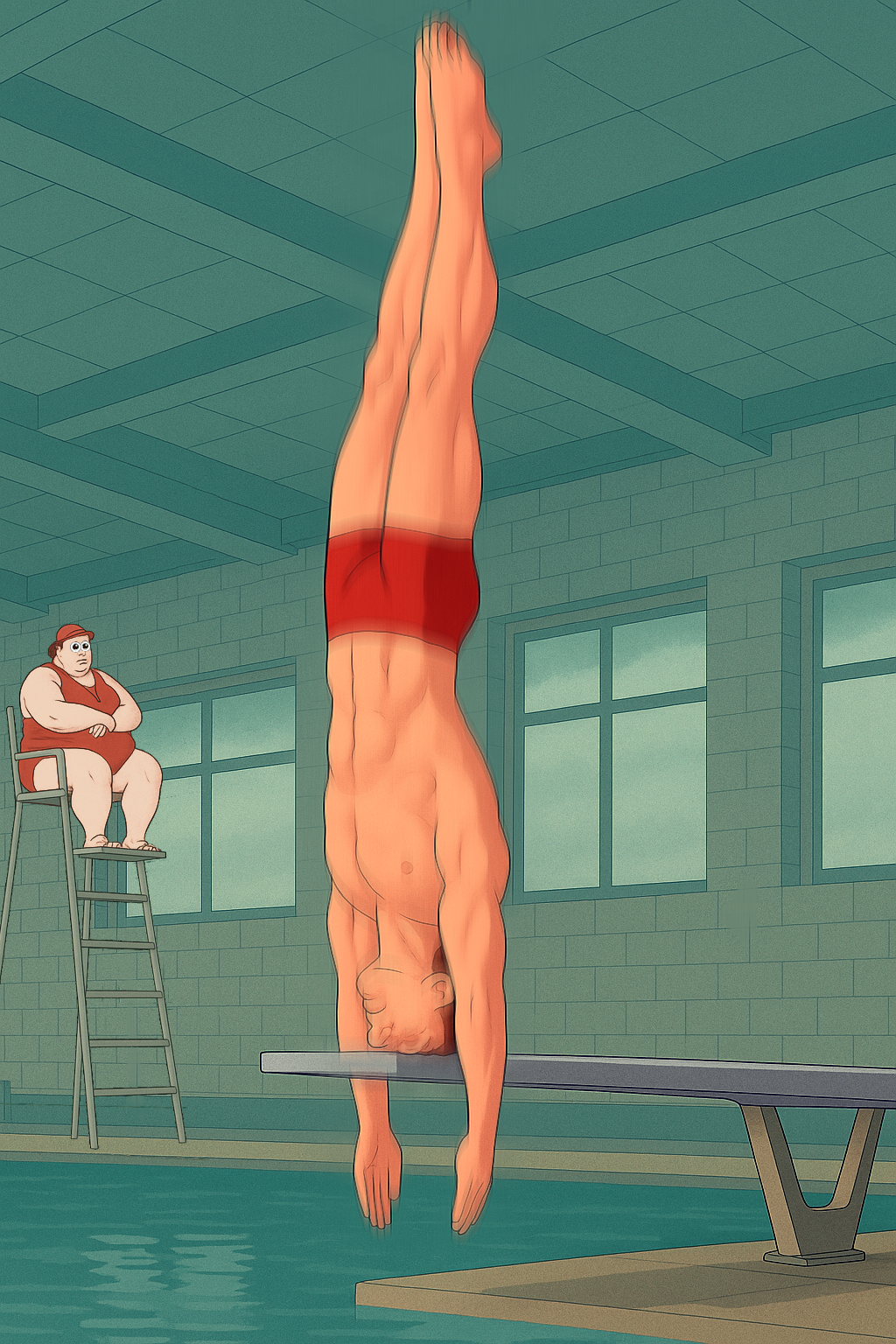

Having no interest in swimming laps, I decided to try out the diving board. I had run cross-country my freshman year. My body was all legs and no fat. I could jump like a frog, but I had no skill in diving.

Someone on the swim team said to me, “Try to go in straighter and get more height.” That made sense.

Lori kept swimming her laps. Tik tok.

I tiptoed to the overhanging end of the diving board, spun around 180 degrees, and hung my heels over the edge. I bounced twice for rhythm and power, then leapt into the air.

A funny thing happens in mid-air when your feet hang high above you, and a fiberglass diving board oscillates directly beneath your head: time slows down.

The lifeguard to my right was a 300-pound Russian woman with a heavy accent, a former swimmer from the USSR. I knew if I struck the board and lost consciousness, I would sink to the bottom like a stone. Could that buoyant lifeguard reach me to pull me out? I had to stay conscious.

As I accelerated toward the board, the world slowed into freeze frames. I struck the board squarely with my face, bounced into the water, maintained consciousness, and swam to the ladder.

Blood sprayed from my nostrils like a harpooned whale.

The lifeguard threw her arms into the air. “Why didn’t you flip backward?” I hardly understood the question. I needed somebody to drive me to the hospital.

Could Lori take me? No. She had a geology exam the next morning. Two other women took me instead.

The Emergency Room doctor used cocaine to stop the bleeding. A few days later, I saw an ENT physician who put twelve shots into my face and crunched the nasal bones open using metal tools. “Don’t look at the instruments,” he said. But I spotted my flesh hanging there and passed out.

A week later in my archeology class, an eight-foot wooden dirt-sifting tripod fell over and struck me directly on the bridge of my nose.

Eventually, a plastic surgeon repaired the fractures. The packing remained in the nose and sinuses for five months.

But prior to the definitive surgery, while wearing just a noseguard over my bruised face, I seized the moment. The college Bible study group had planned a weekend trip to Cedar Point, a famous amusement park in Ohio. I decided I needed to get more direct with Lori.

“I wish you could feel about me the way I feel about you.”

She took pity on me, the poor guy with plug-nosed speech and a blue face. The next day, she rode a roller coaster with me. That’s how our dating life began—with a broken face and a roller coaster ride.

That head injury probably contributed to the fibromyalgia syndrome that torments me to this day. After the diving accident, I could no longer hold a ping pong paddle correctly. My hand quivered uncontrollably. I detected a dropoff in my thinking speed. And over the next ten years, I developed a severe pain syndrome.

But it was worth it. I had won the attention of my bride.

Lori got an A on her geology exam. All the rocks she studied disappeared from her memory save one. She wears it on her finger.

Please consider subscribing to my newsletter!

I need to expand to an audience of 10,000 readers!

If you liked this post, please send it to a friend. If the reading audience grows, agents and publishers become suddenly far more keen on joining in the Adventures of TAT!

Copy URL to Clipboard

3 responses to “The Dive”

What a great story Dr. Thompson well it’s not a story. What a great fact of life the way God has used those circumstances to bring you the joy that you still have today.

Thanks, Yvette. What a mystery. How frequently God builds good things out of broken pieces.

[…] The Dive […]